by Jerry Mikorenda

They say great inventions come to those not looking for them. Afterall, Alexander Graham Bell was trying to build a wireless telegraph when the whole voice carrying thing fell into his lap.

My own sniff at discovery, or adaptation, came a few years ago while researching vacation spots. Nothing big. Just looking for a nice little B&B in a quaint town within a few hours drive from home for a weekend getaway. It also would be an escape from the novel I was attempting to write that would eventually become The Whaler’s Daughter published by Regal House Publishing (Fitzroy Books) last month. I had plot-painted myself into a corner and lacked the leap of faith roller brush to catapult me out. What to do? Start over, change all the characters, drop the whole thing?

The photo of this mystery house was taken somewhere along the Chesapeake Bay shoreline. Eventually a storm destroyed the building. The photographer is unknown.

Googling around harbor villages seemed harmless enough as did the obligatory “images of…” links that popped up. That’s when I saw a postage-stamp sized photo of an odd coastal house. Enlarged, it’s the photo seen here. A once stately home seemingly floating on a bay or in an ocean covered with pelicans (I believe they’re pelicans) lounging on its chimney’s, gables, and roof. It looked like a cocktail party for birds. A lunchtime eureka moment bounced up and slapped me in the face like the tail of a fresh caught mackerel hanging from a fishing-pole hook.

In my mind, this quickly became the Pelican House. A retirement home for old sailors and whalers. A once grand lodge that fell on hard times. Likewise, I discovered, pelicans were rich in symbolism for many cultures. They are considered sacred by many indigenous Australian people. Ancient Egyptians saw them as guardians in the afterlife while Christians saw pelicans as self-sacrificing for the way they treat their young. The Pelican House became a transition place between the spiritual and physical worlds that was habited by eccentric characters who seemed to talk in riddles that made sense later in the story.

Having something concrete before me to write about (the photo) freed me to open my imagination even more so I could expand on what the house meant in the novel. After that, I ended up collecting some sixty odd images relating to the story. Anything from storms and ships to pie floaters and hairstyles. I’m now posting many of these public domain images on my Instagram page to promote The Whaler’s Daughter. Outside of the digital nature of the pictures, creating backstories for objects or art is nothing new.

Called ekphrasis, the word comes from ancient Greek meaning to describe, speak out, or explain an object, usually art. There are more than a few examples of this throughout history. Think of Keats’s Ode on a Grecian Urn or Homer’s (not Simpson) portrayal of Achille’s shield in the Iliad. Ekphrasis-ing is a good tool to use, especially if you want to develop the meaning or symbolism of your story on another level, or if you hit writer’s block. Just look at the photos and start writing. Remember, those pictures are worth at least a thousand words each.

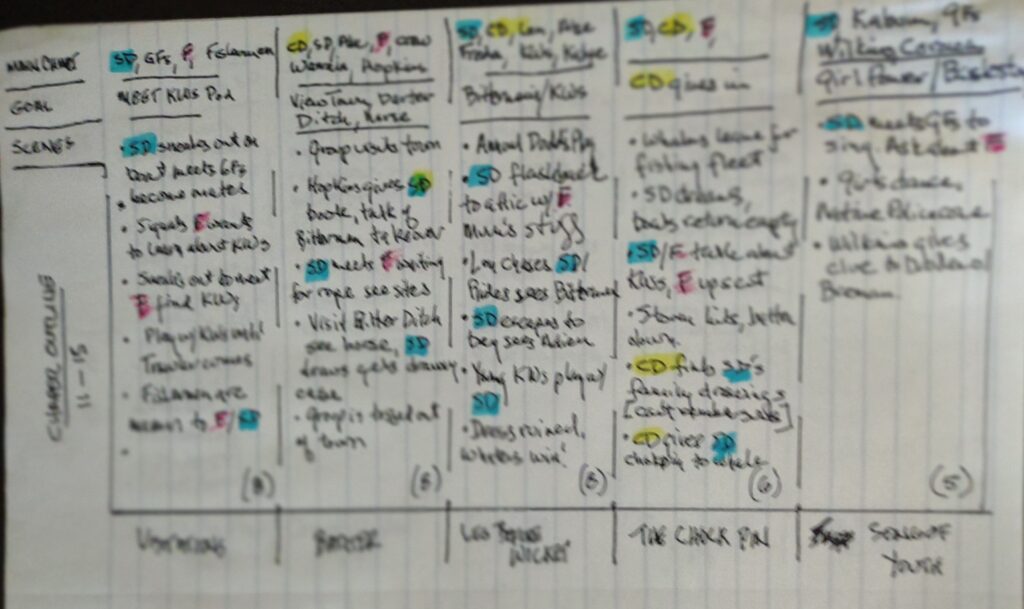

Another useful mapping, or outlining technique, I used during the revision process of TWD is a variation on mind mapping. I had so many characters running around I lost track of who was who doing what with whom. More importantly, that confused readers about what was important in the story. Rather than start slashing scenes and editing on a whim, I wanted a snapshot, a fingerprint, of what was there. If I was going to kill my darlings, I wanted proof they were guilty first. I broke each chapter down to its essential dramatic actions. This was a time-consuming task but well worth it. I called it a Character Action Map (CAM). Think of a card game. You’re dealt a hand. What’s the first thing you do? Put the cards in some sequence or value order. As the game changes the so does the cards you hold and order.

Some of my chapters were excessively long with important dramatic action coming from one-off minor characters. The opening was too long and billowy. I moved several chapters from the back of the book to the front. I took several scenes from the middle and spliced them together as a new first chapter. I was sewing together my very own Frankenstein (or is that Frankensteen?). The map/outline let me eliminate scenes that were too similar and allowed me to overlay the Hero’s Journey, with its midpoint, twists, plot points, etc. Using my CAM to edit made the darling cutting less personal and more mechanical. As you can see, I also color-coded my primary characters actions to get a visual representation of where they were appearing throughout the draft. This allowed me see that I left out one very important factor in the book – my main character’s brothers. They needed to be mysterious, not missing.

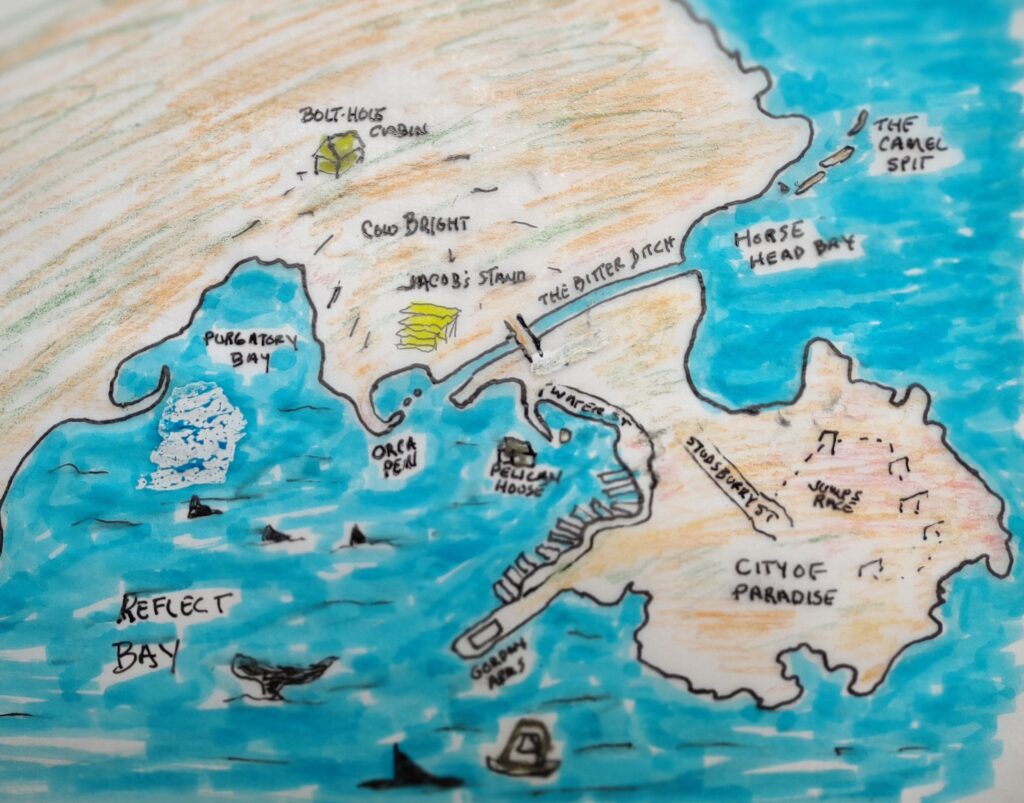

Finally, I would make a case for plain old mapping or chartography. Faulkner used it to create Yoknapatawpha County as did his mentor Sherwood Anderson for Winesburg, Ohio. Here’s a link to some of the more famous maps in literature (link). Mapping is especially useful in world building. In my case, the City of Paradise is based on Eden, New South Wales. I had the shoreline, but I still needed to understand where the action was taking place. I added the fictional topography I invented for the story. Knowing where every nook and rock is adds confidence in your sense of place whether it’s a land mass, town, lake, house, or a street. There’s also something very therapeutic about taking a break from all the ethereal imagining and creating something concrete that you can see, touch, and color!

Add as much detail as you like. But don’t go down the rabbit hole. When I wanted to start measuring everything in kilometers, I knew I had to stop mapping and start writing again.

Jerry Mikorenda’s biography America’s First Freedom Rider: Elizabeth Jennings, Chester A. Arthur, and the Early Fight for Civil Rights was published by Rowman & Littlefield in 2020. His short stories have appeared in Cowboy Jamboree, BULL, Gravel Magazine, and the San Francisco Chronicle among other magazines. His nonfiction has appeared in The New York Times, Newsday, The Boston Herald, and the Encyclopedia of New York City. The Whaler’s Daughter is his first novel.

Talk about a broad statement. When I first started writing I found that edict vague and annoying. I didn’t want to write what I knew. What I knew was boring. I wanted to write about worlds that were outside the little province of Kaltman. Outlandish worlds. Fantasy worlds. Dramatic worlds. Wasn’t that what fiction was about?

Talk about a broad statement. When I first started writing I found that edict vague and annoying. I didn’t want to write what I knew. What I knew was boring. I wanted to write about worlds that were outside the little province of Kaltman. Outlandish worlds. Fantasy worlds. Dramatic worlds. Wasn’t that what fiction was about? Whether you write the next great American novel, or manage to find that elusive ending to a 500 word story. Whether you’re surfing hurricane swells in Maui, or shore break slop in Rockaway. If you’ve traded in cool and correct for marvelous and extreme, then you’re already the best writer or surfer you’ll ever be.

Whether you write the next great American novel, or manage to find that elusive ending to a 500 word story. Whether you’re surfing hurricane swells in Maui, or shore break slop in Rockaway. If you’ve traded in cool and correct for marvelous and extreme, then you’re already the best writer or surfer you’ll ever be.