Every good story needs a setting; the story of me began on a farm in Rock Island County, Illinois. I grew up thinking everyone lived in old places that held mysterious secrets. Our family farmhouse stood on a hill overlooking the Meredosia Bottoms, a flat expanse of sediment-rich land where the Mississippi River overran its banks centuries ago and connected with the Rock River.

The house was over a hundred years old, according to my parents, as were many of the outbuildings—barns, sheds, the corn crib, the outhouse. My grandfather owned the place before he passed it on to my dad, but before Grandpa, a man named Johnny had lived there. We knew this because he’d painted his name inside the walls of the structure we used as a garage. My parents told us that he’d died in the 1950s in a farming accident, in what was now our garden.

This information was unsettling for kids to hear, but also fascinating.

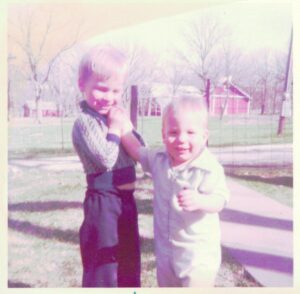

When we were old enough to wander unsupervised, my brothers and I would explore the property, like amateur archaeologists. We discovered: crumbling masonry where a creek was dammed decades earlier, a black horse-drawn carriage rotting in the corner of a barn, and a mummified cat who’d had the misfortune to die on top of an open bag of dry cement. A rock wall ran perpendicular to an outdoor root cellar, and one day while trying to dig under it we discovered a trove of vintage glass bottles—someone in the 1910s had buried their garbage there.

(Why were we trying to dig under the wall? We were looking for a bat skeleton. It’s a long story.)

The inside of the house held strange secrets, too. A closet under the stairs had an angled ceiling, so that behind the coats was a little wedge-shaped alcove, dwindling into nothing like a reverse Narnia. The third step in the attic staircase was loose, and if you pulled on the wooden nosing, the hollow box underneath was perfect for hiding things.

It was a fine place for a writer to grow up. I think I internalized the idea that every place has a history, that if you just look hard enough, you can see the influence of the past on the present. (Our farm might never have been a farm if the Mississippi hadn’t left nutrients in the soil hundreds of years earlier!)

I live in California now, in a townhouse that is roughly the same age as me, and like a lot of Americans, I spent much of 2020 at home. I taught online college courses, I lectured over Zoom, I tried out a bunch of new recipes with my boyfriend, and I finished my debut novel, Maybe There Are Witches.

The setting for my book is an Illinois village called Biskopskulla, which was inspired by a real place, Bishop Hill, not far from my family’s farm. As a kid, I was intrigued by Bishop Hill, which was founded in 1846 by a cult-like religious sect from Sweden. The town is now a national historic site, and it represents a very particular kind of Americana: a tourist destination without many tourists.

I visited Bishop Hill before the pandemic when I was starting my novel. It’s a beautiful place; you can tour the old church and even visit the original colony cemetery, which contains graves from the first harsh 1846 winter right up until today. If you look around the cemetery, you can find the marker for the grave of the sect’s leader, Eric Jansson, who was murdered in public and buried days later after he failed to resurrect. You can even find a few wooden grave markers, which have not been commonly used in cemeteries for a very long time. These have deteriorated so that no details remain. Who do they commemorate? When did this person live? When did they die? It’s a mystery.

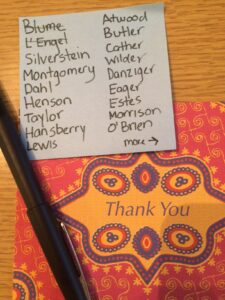

I love a good mystery, and I’m captivated by old places with hidden secrets, which must be why I like to write about them. I’m grateful to the folks at Fitzroy Books who selected my novel, Maybe There Are Witches, as the winner of the Kraken Book Prize for Middle Grade Fiction. It’s the story of a thirteen-year-old girl who moves into an old house in a small town with a dark history. In the basement, she finds a buried book, written by a woman who was executed for witchcraft. I am beyond excited that this book will soon be available for young readers and anyone else who enjoys a spooky tale.

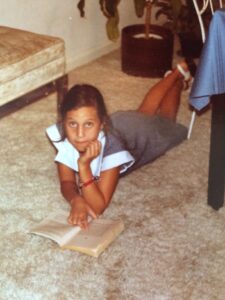

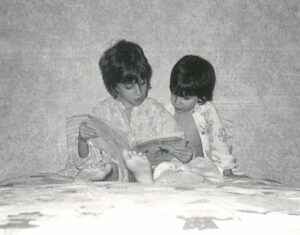

If I wanted to split hairs, I’d clarify that Maybe There Are Witches will be my debut published novel, but my first novel was actually written on the farm the summer after my twelfth birthday. If you’ve read this far, you won’t be shocked to learn it was set in a creepy old house. In it, a pair of kids find themselves inexplicably invited to the reading of a famous author’s will. They’re tasked with solving a mystery as they compete against other potential heirs to find clues in every room of the author’s mansion. That book was written out longhand in notebooks and then typed on an IBM electric typewriter. I am certain that it was embarrassingly bad. As far as I know, no copy of that tale exists today.

But if one does, it’s probably in a box in the farmhouse attic. Or hidden under the attic stairs, third step from the bottom. Or buried in a time capsule under a stone wall, waiting.

Jude Atwood is a full-time community college professor, who teaches mass communication and media literacy classes, and was honored with the Legacy Award from the American Readers Theater Association for contributions to the art of readers theater. His fiction has appeared in Broadside and Literally Stories, and his first novel, Maybe There Are Witches, won the 2021 Kraken Book Prize for Middle Grade Fiction.