by Gary Pedler

When writers explain how they came to write a book, they often talk about “the germ of an idea.” For me, it’s usually more a matter of several germs coming together. Fittingly, the first germ of an idea for my novel Amy McDougall, Master Matchmaker appeared in the midst of trying to make a match. A match for myself.

One day my friend Milam telephoned. He’d attended a meeting of a group called Gay Future Dads. “Girl!” Milam called all his gay friends “girl.” “Girl! You need to get yourself to one of these meetings. That’s where all the eligible men are.” Milam’s reasoning was that gay men who wanted to have children were more likely to be emotionally mature and financially sound.

Since in the past I’d usually been glad when I took Milam’s advice, I showed up at the next meeting of GFD. It was hosted by a couple at their home in San Francisco’s Corona Heights. On our name tags, we identified ourselves with a red dot for coupled or a green dot for single. To cover all possibilities, a blue dot for “confused” was also available.

In the beginning, I felt like a fraud participating in the group since in truth I was there on a man hunt and had never given much thought to having children. Besides, at fifty, I considered myself too old. When we went around the room and introduced ourselves, the best I could do was say that I was “thinking about thinking about becoming a parent.”

A woman from Our Family Coalition made a presentation, standing in front of the fireplace. She explained that one way gay people could have children was to adopt kids who were in foster care. In the Bay Area, she said, gay parents accounted for the majority of such adoptions. I learned there was even a city agency that encouraged these. While I might not have been interested in having kids myself, as the woman talked, the writer in me thought, That’s an interesting phenomenon, gays adopting kids.

Despite my best efforts, I failed to make a date with any of the men at the gathering. However, I did have an interesting talk with a guy named Jeremy. Like several of the guys, Jeremy wasn’t a future dad, but an actual one. He’d adopted two girls, who were nine and thirteen at this point. He’d always wanted to have children ever since he was little, he told me. “When I played house with my two brothers, I was always the mom and always had kids.” Despite coming out in his twenties, he’d held to this trajectory. The only shift was realizing he wouldn’t have kids with a woman.

Attending the meeting and hearing Jeremy’s story was the first germ of an idea. Over the next week, a second germ appeared, attaching itself to the first. This was The Courtship of Eddie’s Father, a movie starring Glenn Ford from the early sixties that a few years later inspired a TV series with Bill Bixby. I’d watched the series often enough to have the premise firmly implanted in my brain: a young boy tries to find a new wife for his single father and much laughter ensues. These two germs combined to form The Courtship of Amy’s Father. The early twentieth century twist was that a girl decided to find a new boyfriend for the single gay dad who’d adopted her.

Seeing Jeremy at the next meeting of GFD, I told him about the story I wanted to write and asked if I could interview him to get more details. He agreed. During our first interview, Jeremy gave me a fuller account of how he’d become a parent. Some things I learned from him were of a technical nature, like how a single person went about adopting a child.

At the end, we agreed to meet a second time. I made a list of additional questions I wanted to ask. However, I could never pin Jeremy down for that second interview. I’ve always wondered whether I could have gotten even more great ideas from him if only I’d managed to meet with him that second time.

At first, perhaps through association with the film and series, I saw Courtship as a screenplay. Since I had no connections with the film world, after six months of work, I admitted it would be more pragmatic to write the story as a novel instead, a novel for young adults. At the time, I was hearing from my writer friends that YA was the one thing agents and editors were actually looking for, our best chance of getting published.

At times this subject matter seemed beyond me. How could I possibly write from inside the mind of a fifteen-year-old girl? I lived across the street from the high school that Amy attended in the story. I imagined offering my services as a tutor in order to have a chance to talk with some teenage girls. This might have been a good idea. However, as I worked, I became convinced I could find much of the character inside me. Echoing the words of Flaubert regarding his creation Madame Bovary, I declared, “Je suis Amy McDougall!” I am Amy McDougall!

The plot flowed well, too. Halfway through, I had a moment of feeling stumped. The story-line didn’t seem involved enough for a full-length novel. But soon I came up with an idea. Amy had made a match between her dad and her Spanish teacher Enrique Diaz, who was from Puerto Rico. I had the three of them fly off to Puerto Rico for their summer vacation and stay with Enrique’s mother Pilar in San Juan.

At around this time I found an excellent critique partner, Margo. Margo was a dedicated YA author, whereas I saw myself as a writer for adults venturing outside my home territory. Margo not only helped me develop a suitable YA style. As a mother of modern-day teenagers, she helped me avoid some embarrassing factual errors. For example, when I mentioned a chalkboard in a classroom, she explained that chalkboards were out and white boards in.

Finishing the book after a couple of years of work, I sent it to agents. And sent and sent and sent. I can’t say how many agents I queried because I’m not the sort of person who likes to torture myself by making such calculations. Let’s just say I queried many.

Finally, an agent offered to represent me, and not just any old agent. She worked for a well-known agency in New York and clearly knew her business. The agent made suggestions about how I should change the manuscript. I complied with almost all of them. Since I didn’t consider myself a full-fledged YA writer, I was more willing to listen to people’s suggestions than I might have been regarding a piece of adult fiction.

When the agent considered the novel fit for presentation to the world, she sent it to a dozen editors, most at major publishing houses. My spirits soared! Then the responses came in. The results, detailed in a spreadsheet the agent had prepared, made my spirits droop. While there were some near misses (“Too bad, we just published something similar”), there were no hits.

Before the agent sent the book out to a second batch of editors, she told me we needed to act on the comments of the rejecting ones. A comment that had appeared several times was that Amy seemed too young for fifteen. Too young! How could that be when my constant worry had been that she would sound too old because I, the author, was so much older than she was? Maybe I’d overcompensated.

The agent suggested reducing Amy’s age. I tried fourteen. No, that was too close to her original age. All right, thirteen then. That might not seem a big change to those who aren’t familiar with the YA world. Those who are will realize that to make the main character thirteen changed the audience from YA to Middle Grade. Especially after the editors’ rejections, I doubted my mastery of a YA style. Now I needed to get a handle on an MG style, which was yet further from an adult one.

Later, an even bigger challenge arrived in an email from the agent. Her new idea was that I’d actually written two stories, the one that took place in San Francisco and the second set in Puerto Rico. Even as I’d written the second part, I’d suspected I was going against the typical YA storyline in which the entire thing took place in one basic setting (road trip stories being an exception). In Puerto Rico, I also introduced a number of new characters. In a novel for adults, this might have seemed like a good idea. In YA/MG land, maybe not.

I found I could work with Amy shedding some years. On the other hand, cutting out the entire second half of the original story was the most painful experience of my writing life. It was like losing a limb, and afterward I was still aware of the phantom one. Pilar disappeared, as did Darren, a romantic interest for Amy, and a trio of American girls whom Amy nicknamed Sugar, Honey, and Candy. Gone was the funny scene where Darren got drunk at his sister’s wedding in San Juan and fell into the swimming pool while Amy, Sugar, Honey, and Candy looked on aghast.

Even the original title got tossed out. Margo had already expressed doubts about it. “Your young readers won’t get a reference to some film from the sixties,” she said. Both she and my agent approved my rechristening the novel Amy McDougall, Master Matchmaker. It did seem providential that I’d already given my heroine a last name that started with “m,” giving the title some euphony.

Just as painful as losing half of the original story was having to come up with a new second half, especially since by now I was a little gun shy. Did I know how to write YA/MG? Did I know how to write at all?

However, I’m a writer who always finishes my projects, my full-length ones anyway, and I was determined to see this one through. Bad enough to see Sugar, Honey, and Candy become phantoms. Much worse to have my beloved Amy share the same fate.

The agent sent out Amy McDougall to the next batch of editors. Still no one bit. The agent said she couldn’t resubmit it to any of the agents in the first batch despite its drastic makeover. That was against the rules.

Then I got the email from an agent that writers dread, the one saying she wouldn’t send out the manuscript anymore; she’d exhausted all possibilities. She asked if I was working on anything else. I told her I was, another YA novel. More bad news: the agent didn’t like the chapters I sent her from the new book. Did I have anything else? No, sorry, I didn’t. By now, the agent-writer romance appeared to be cooling off. Instead of letting it have a drawn-out, ambiguous end, I officially terminated with her.

Agent-less, I sent Amy out on my own. Again, I didn’t keep count, but as before, there were many rejections. Periodically, I would read the manuscript afresh, wondering if the rejections meant the book wasn’t any good. Instead, each re-reading confirmed my feeling that it was good, quite good in fact. I loved the new second half. I even loved Amy being thirteen. Maybe my mind worked more like a thirteen-year-old’s than that of a person with greater maturity.

The happy ending to this story was that the kind folks at Regal House accepted Amy McDougall, Master Matchmaker for publication. I’ve been excited by all the stages of its production. First, the cover, with Amy’s face looking out at me, pretty much as I’d imagined her. Next the ARC. For non-writers, I’ll explain this stands for Advance Reader Copy. For writers longing to see their manuscript become an actual book, it’s a gorgeous rainbow ARC in the sky. Finally, with a big triumphant cymbal crash, the actual book will finally appear – on April first, unless this is all an elaborate April Fool’s gag life is playing on me.

I never succeeded in making a romantic match for myself with any of the Gay Future Dads. At least, years later, I did make an author/publisher one.

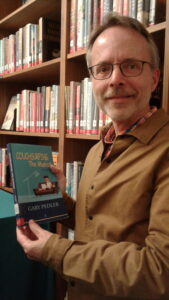

Gary Pedler is the author of the travel memoir Couchsurfing: the Musical. Gary’s stories have appeared in The Missouri Review, The Berkeley Fiction Review, Bryant Literary Review, the anthology Outer Voices, Inner Lives, and other publications. Amy McDougall, Master Matchmaker is his debut work of fiction for the middle grade market.